BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://jsurgery.bums.ac.ir/article-1-443-en.html

, Mahsa Pourdavar

, Mahsa Pourdavar

, Mohammad Rasul Asadi

, Mohammad Rasul Asadi

, Hosseinali Rahdari

, Hosseinali Rahdari

, Sadra Amirpour Haradasht *

, Sadra Amirpour Haradasht *

Abstract

Introduction: Fractures of the nose and lower jaw are common injuries. Given that dentists may encounter these types of injuries, it is crucial to know this area. This study aims to evaluate the level of knowledge among general dentists and dental students from Zahedan on the diagnosis and initial management of mandibular fractures.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included 200 general dentists and final-year dental students who were conveniently selected and examined through a researcher-made questionnaire. To determine and select samples proportional to the population size in each stratum (dentists and students), the quota for each was determined. Then, to select samples in each stratum according to the inclusion criteria in an easy and accessible manner, sampling was conducted from each stratum. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26), independent t-test, and Chi-square statistical test.

Results: The mean age of the students was 24.4±6.2 years, while the mean age of the dentists was 36.6±8.4 years. In terms of gender distribution, male students made up 46.2% of the participants, while female students comprised 53.8%. Among general dentists, 43.6% were male, and 66.4% were female. The average working experience in general dentists was 9.4±3.1 years. Of the participants, 139 (69.5%), 14 (7%), 20 (10%), 18 (9%), and 9 (5.5%) mentioned motor vehicle accidents, fights, sports injuries, falls, and iatrogenicity following surgery as the most common causes of mandibular fractures, respectively. The level of knowledge about fracture management and care was significantly related to job position (P=0.03) and work experience (P=0.04).

Conclusion: The level of knowledge among dental students and dentists regarding mandibular fractures, their diagnosis, and initial management is inadequate. Therefore, students and dentists should be trained in this field before graduation, and their training should be updated regularly.

Key words: Dental students, Dentists, Mandibular fractures

Introduction

Fractures involving the nose and lower jaw are frequently encountered injuries. While most nasal fractures can be managed without surgery, surgical treatment is often necessary for mandibular fractures due to the intricate anatomy and function of the jaw. The mandible, being a movable bone, is prone to multiple fractures, with a risk of contamination from normal oral bacteria. Additionally, adjacent teeth may be affected, and in some cases, mandibular fractures can lead to respiratory issues in the patient (1).

The mandible, nasal, and zygomatic bones are frequently fractured due to facial trauma from falls, fights, or car accidents. Patients with mandibular fractures should be evaluated for potential injuries to the cervical spine and brain (2).

Third molar surgery is a common facial surgery in the field of dentistry. However, it can be associated with various complications (3, 4). The most common complications following mandibular third molar surgery are nerve damage, dry socket, infection, bleeding, and pain. Less common complications include severe jaw stiffness, damage to the adjacent tooth, and accidental jaw fractures (5).

Facial fractures constitute approximately 15% of emergency visits in general. However, the occurrence rate of iatrogenic mandibular fractures resulting from mandibular third molar surgery has been reported to range from 46 to 75 per one hundred thousand cases (6, 7). Regarding gender distribution, research indicates that male patients over the age of 40 face a higher risk of mandibular fracture (8).

Identifying the symptoms and causes of mandibular fractures is essential. Patients often experience jaw pain, facial asymmetry, facial deformity, and difficulty swallowing. Other possible symptoms include misaligned teeth, limited jaw movement, jaw stiffness, or numbness in the lower lip (9).

Hence, during the physical examination, it is essential to assess the jaw and facial region for any signs of deformity, such as ecchymosis and edema (10). During an intra-oral examination, it is crucial to check for malocclusion, trismus, and facial asymmetry. Assessing the patient's occlusal status before surgery can be difficult, but dental records, if accessible, can be a helpful reference for fracture reduction (11).

Diagnosing mandibular fractures requires X-rays, including a series of images, a panoramic view, and a CT scan. The series of images includes views from the front, sides, and top, which help examine the jaw joint and its connecting area (12).

A panoramic X-ray is better for examining fractures in the front and body of the jaw. A CT scan is recommended if there are possible fractures in other facial bones. For patients who are unconscious and have missing teeth, a chest X-ray is needed to check for aspiration. Blood tests are usually not necessary, but in certain cases, basic tests, such as a complete blood count and INR, may be done for patients taking blood thinners (13).

In 2017, Pickrell et al. conducted a study on mandibular fractures in Texas, USA. They found that mandibular fractures are a significant part of maxillofacial injuries and their evaluation, diagnosis, and management remain challenging despite advances in imaging technology and fixation techniques. Proper surgical management can prevent complications, such as pain, malocclusion, and trismus. Open and closed surgical reduction techniques can be used based on the type and location of fractures (14).

Previous studies indicate that mandibular fractures are common in the jaw and face, often caused by road accidents. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is the preferred method for diagnosing mandibular fractures. Panoramic radiography has a limitation of presenting fracture lesions separately (15).

In 2019, Hassanein et al. conducted a study in Saudi Arabia to evaluate the methods and results of mandibular fracture management, and in this study, 1,371 patients were studied. The results of this study showed that the most common cause of mandible fracture was road accidents and falling from a height. Also, in this study, more mandible fractures were observed in young people, and the most common treatment used for mandibular fractures was open surgery and internal fixation (16).

In their 2021 study "Mandibular Fractures: Diagnosis and Management," Panesar et al. from Washington, USA highlighted the need for accurate evaluation, diagnosis, and management of mandibular fractures to restore facial aesthetics and functionality. Understanding surgical anatomy, fracture fixation principles, and specific fracture characteristics in different patient populations can prevent such complications as malocclusion, non:union:, and paraesthesia (17).

Mandibular fractures are a common type of facial injury, often resulting from accidents, assaults, or falls. The ability to diagnose and treat these fractures effectively is essential for oral and maxillofacial surgeons and general dentists. Considering the aforementioned information and recognizing the significance of mandibular fractures, as well as the lack of comprehensive studies in this area within Zahedan, our study aims to investigate the level of knowledge among general dentists and final-year dental students in Zahedan during 2023. This group is often one of the first to evaluate patients with isolated lower jaw fractures, and they need to possess knowledge regarding the diagnosis and initial management of mandibular fractures. The findings of this study can be valuable in formulating strategies to enhance dentists' awareness and subsequently reduce the complications associated with such fractures.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.ZAMUS.REC.1402.288). This cross-sectional study included a total of 200 final-year dental students and general dentists. Data collection for this study involved interviews and the administration of questionnaires, using information forms and researcher-made questionnaires. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire about the diagnosis, treatment, care, and management of mandibular fractures were previously confirmed in a separate study in Iran (18). Minor modifications were made to the questionnaire, and its validity was assessed by evaluating the Content Validity Index (CVI) and Content Validity Ratio (CVR) with the input of six experts, resulting in 73% and 78%, respectively. Additionally, the questionnaire's reliability was established through its completion by 36 individuals from the research population, yielding a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.79.

Sample selection was carried out based on the population size within each group (dentists and students), with the allocation of proportional representation. Simple and accessible sampling methods were employed to select participants from each group according to predetermined criteria. Based on a previous study (18) indicating that only 16% of dentists demonstrated accurate knowledge regarding mandibular fractures, and considering a Type I error of 0.05 and a maximum acceptable difference of 0.05 (d=0.05), a minimum sample size of 200 individuals was determined using the following formula:

Participants were recruited if they met the following criteria: being a licensed general dentist or a final-year dental student, residing in Zahedan, and expressing a willingness to participate in the study. Individuals were excluded from the study if they were unwilling to complete the post-interview questionnaire.

Subsequently, the questionnaires and information forms were distributed to the research units either in person or online, and collected upon completion. To control for confounding variables, only individuals who expressed full willingness and had sufficient time to participate in the study were included, after receiving detailed explanations about the study and its procedures. Ethical considerations were upheld, and answer sheets and responses were provided to both the students and dentists.

The questionnaire consisted of questions related to the diagnosis, treatment, and causes of mandibular fractures, with each question having a correct answer. The frequency distribution of the answers to each question determined the level of knowledge among the dentists. In terms of the management of mandibular fractures, six questions were asked, with three correct answers indicating low knowledge, four to five correct answers denoting average knowledge, and six correct answers indicating good knowledge. Nine questions were posed regarding the care of mandibular fractures, with three correct answers reflecting low knowledge, four to seven correct answers representing average knowledge, and eight or nine correct answers signifying good knowledge.

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26). The data were initially checked for quality. Descriptive statistics like frequencies, means, medians, standard deviations, and interquartile ranges were calculated to summarize the data. The study also estimated average scores and frequencies of knowledge, practice, and attitude. It should be noted that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess normality. Frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were used to describe the data through tables and statistical charts. Independent t-test and Chi-square test were employed to determine relationships and analyze the data. In all analyses, a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study examined 200 individuals from the community of general dentists and final-year students of dentistry in an easy and accessible way. Specifically, the study examined 94 general dentists and 106 final-year students from Zahedan Faculty of Dentistry who met the entry criteria.

The mean age of the students was 24.4±6.2 years, while the mean age of the dentists was 36.6±8.4 years. In terms of gender distribution, male students made up 46.2% of the participants, while female students comprised 53.8%. Among general dentists, 43.6% were male, and 66.4% were female. The average working experience in general dentists was 9.4±3.1 years.

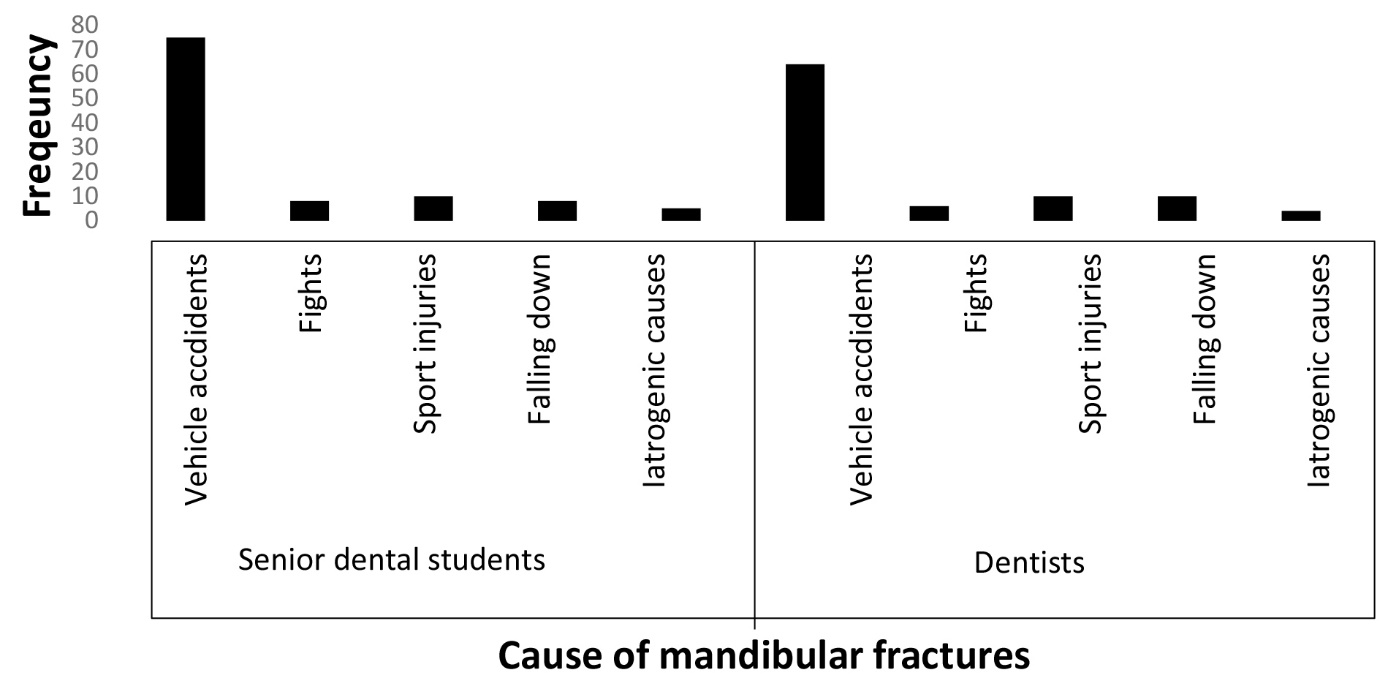

The study found that the most common cause of mandibular fracture was motor vehicle accidents (69.5%), followed by fights (7%), sports injuries (10%), falls (9%), and iatrogenicity following surgery (4.5%) (Figure 1). Clinical examination (9%), panoramic radiography (71.5%), CBCT (9%), and MRI (10.5%) were mentioned as the most reliable diagnostic tools and methods for mandibular fracture.

Regarding the primary treatment for patients with mandibular fractures, antibiotics (5.5%), painkillers (4%), fixation (73.5%), and surgery (17%) were mentioned as the primary treatment options. None of the participants mentioned the option of non-intervention (Figure 2).

The Chi-square test results showed that the distribution of answers to the question about the causes of mandibular fracture, diagnostic method for mandibular fracture, and initial treatment for patients with mandibular fracture was not significantly different between students and general dentists. Additionally, this test showed that the frequency distribution of answers did not differ significantly according to gender or work experience.

Figure 1: Frequency distribution of responses of general dentists and senior dental students to the most common causes of mandibular fractures

Figure 2: Freqeuency distribution of respones of general dentists and senior dental students to the primary treatment of mandibular fractures

In terms of knowledge regarding mandibular fracture management, 29.5% of participants had low levels of knowledge, while 36.5% had high levels of knowledge (Table 1). Regarding knowledge of mandibular fracture care, 21% had low levels of knowledge, while 41.5% had high levels of knowledge (Table 2).

The Chi-square test results also showed a significant difference in the level of knowledge regarding both mandibular fracture management and care between students and general dentists (P<0.05), with general dentists having a higher level of awareness.

Table 1: Frequency Distribution of Knowledge among Final Year Students of Zahedan Dental School and General Dentists Regarding the Management of Mandibular Fractures by Gender, Job Position, and Work Experience

| Total n (%) |

Average n (%) |

Good n (%) |

Low n (%) |

Knowledge Independent variables |

||

| 0.19 | 90 (100) | 32 (31.3) | 30 (43.7) | 28 (25) | Male | Gender |

| 110 (100) | 41 (28.6) | 38 (46.6) | 31 (25) | Female | ||

| 0.03 | 94 (100) | 43 (21.4) | 31 (45.1) | 20 (23.5) | General Dentist | Job Position |

| 106 (100) | 30 (28.3) | 37 (44.4) | 39 (30) | Final Year Students | ||

| 0.04 | 63 (100) | 12 (11.8) | 25 (52.9) | 26 (35.3) | Under ten years | Work Experience (year) |

| 31 (100) | 16 (37.2) | 10 (41.8) | 5 (20.9) | Oven ten years | ||

Table 2: Frequency Distribution of Knowledge among Final Year Students of Zahedan Dental School and General Dentists Regarding the Care of Mandibular Fractures by Gender, Job Position, and Work Experience

| Total n (%) |

Average n (%) |

Good n (%) |

Low n (%) |

Knowledge Independent variables |

||

| 0.21 | 90 (100) | 36 (31.3) | 35 (43.7) | 19 (25) | Male | Gender |

| 110 (100) | 47 (28.6) | 40 (46.6) | 23 (25) | Female | ||

| 0.03 | 94 (100) | 50 (21.4) | 28 (45.1) | 16 (23.5) | General Dentist | Job Position |

| 106 (100) | 33 (25.6) | 47 (44.4) | 26 (30) | Final Year Students | ||

| 0.04 | 63 (100) | 20 (11.8) | 28 (52.9) | 15 (35.3) | Under ten years | Work Experience (year) |

| 31 (100) | 16 (37.2) | 5 (41.8) | 10 (20.9) | Oven ten years | ||

It appears that most students and general dentists in Zahedan are aware of the primary cause of mandibular fractures, with no notable differences between the two groups. Therefore, in regions, such as Sistan and Baluchistan, where road accidents are prevalent, knowledge about mandibular fractures becomes doubly important.

In terms of the most reliable diagnostic tool for mandibular fractures, clinical examination was mentioned by 18 (9%) individuals, panoramic radiography by 143 (71.5%) individuals, CBCT by 18 (9%) individuals, and MRI by 21 (10.5%) individuals. The distribution of answers regarding the diagnostic method for mandibular fractures did not differ significantly between students and general dentists, nor did it vary based on gender. These findings align with a study performed by Mehdizadeh (20).

Overall, more than 71% of both students and dentists correctly identified the diagnostic method for mandibular fractures, indicating sufficient knowledge in this area. However, it is essential to focus on dentists' performance in managing and caring for these cases, necessitating periodic training. Additionally, students exhibited comparable knowledge to dentists concerning the correct diagnosis method for fractures, highlighting the adequacy of their knowledge in this field.

Of the 200 participants surveyed, 11 (5.5%) and 8 (4%) individuals mentioned antibiotics and painkillers, 147 (73.5%) individuals suggested fixation, while 34 (17%) individuals believed that surgery was the primary treatment option. There were no significant differences in the distribution of answers between students and general dentists or based on gender. Overall, students and dentists in Zahedan exhibited good knowledge regarding the initial treatment of mandibular fractures. However, it is essential to ensure that all dentists possess the necessary knowledge and skills to manage and care for patients with mandibular fractures.

In this study, the researchers examined the knowledge levels of participants regarding the management and care of mandibular fractures. Out of the total 200 participants, it was found that 59 (29.5%) individuals had low levels of knowledge, 68 (34%) individuals had medium levels of knowledge, and 73 (36.5%) individuals had high levels of knowledge about mandibular fracture management. Similarly, 42 (21%) individuals, 75 (37.5%) individuals, and 83 (41.5%) individuals had low, medium, and high levels of knowledge, respectively, regarding mandibular fracture care.

These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted by Mehdizadeh (19) and Nardi et al. (15), but they differ from the results reported by Tabrizadeh (21) and Panesar (17). It is worth noting that these inconsistencies might be attributed to variations in evaluation methods, sample sizes, and research conditions. However, what is clear is that due to the prevalence of accidents and subsequent mandibular fractures in our country, dentists must possess a high level of awareness and competence in managing such cases.

While not all dentists are primary therapists for these types of fractures, in low-income areas where maxillofacial specialists and medical professionals may not be readily available, dentists can play a vital role as initial guides in treating these patients. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to enhance the knowledge and performance of general dentists in this field. This training can begin during dental school through specialized workshops dedicated to mandibular fracture management and care. By providing dentists and dental students with comprehensive education in this area, we can effectively minimize the consequences of mandibular fractures.

The findings of this study revealed a significant disparity in the knowledge levels between students and general dentists regarding the management and care of mandibular fractures. General dentists exhibited a relatively higher level of knowledge, compared to students. Moreover, among general dentists, those with extensive work experience demonstrated a significantly higher level of awareness than those with limited work experience. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted by Mehdizadeh (22) and Fasoyiro in the United States (23).

However, practical experience and exposure to patients with mandibular fractures in emergency rooms or workplaces contribute to an increase in dentists' awareness and performance in managing and caring for such cases. Therefore, it is imperative to provide practical training and workshops in hospital emergency rooms for final-year dental students.

Molashahi's study (24) on general dentists in Zahedan revealed an average level of knowledge concerning emergency conditions in dentistry. Similarly, this study highlights that most students possess average knowledge regarding the management and care of mandibular fractures. This issue persists not only among students but also among dentists at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. However, gaining work experience and entering the labor market will likely improve dentists' performance in this area.

To enhance dentists' awareness and performance regarding medical emergencies and emergency conditions in dentistry, such as mandibular fractures, theoretical classes and training seminars alone may not suffice. Instead, teaching medical emergencies practically on human models, using films and animations about emergency management in dentistry, and practicing emergency management through the simulation of emergency conditions can be effective in improving students' and dentists' awareness and preparation (15, 19).

One limitation of this study is the reliance on questionnaire data, as the questionnaire format may have encouraged participants to provide socially desirable responses. To mitigate this bias, questionnaires were collected anonymously. Additionally, this study was conducted solely in Zahedan, and generalizing the findings to other regions of the world should be done with caution. Therefore, it is recommended to investigate the knowledge and performance of dental students and general dentists in various cities to inform potential reforms in dental education.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that both students and general dentists possess an average level of knowledge regarding the management, treatment, and care of mandible fractures. However, general dentists exhibit a better understanding of managing and caring for these fractures than final-year students. This difference is likely due to general dentists' work experience and practical exposure to treating patients in clinics. To improve students' knowledge and skills in this area, it is essential to review the content presented to them and provide practical classes and workshops. Emphasizing practical training will enable students to gain valuable experience in managing and caring for patients with mandible fractures.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Received: 2024/07/3 | Accepted: 2024/10/14 | ePublished ahead of print: 2024/11/2 | Published: 2025/01/4

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |