BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://jsurgery.bums.ac.ir/article-1-491-en.html

Abstract

Introduction: Developing effective and targeted therapeutic strategies for peritonitis and postoperative abdominal adhesions is essential to mitigate severe sequelae, including intestinal obstruction and infertility. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of intraperitoneally administered tannic acid and selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) in controlling experimental intraperitoneal adhesions in rats, leveraging their potential anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

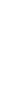

Methods: This experimental study included 30 adult male rats randomly divided into five equal groups: sham group (only laparotomy of the rats was performed without experimental adhesion induction), control group (experimental adhesion induction without any therapeutic intervention), SeNPs group (intraperitoneal administration of SeNPs after induction of peritoneal adhesion), tannic acid (TA) group (intraperitoneal administration of tannic acid after induction of peritoneal adhesions), and selenium nano tannic acid (SeNTA) group (intraperitoneal administration of SeNPs containing tannic acid after induction of peritoneal adhesion). Seven days after the induction of peritoneal adhesions, abdominal adhesion rates and histopathological parameters were investigated and compared among the different groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results: Abdominal adhesion formation was significantly reduced in the TA and SeNTA treatment groups compared to controls (P = 0.01), while SeNPs showed no significant improvement (P = 0.121). SeNTA demonstrated superior efficacy among treatments with significantly lower adhesion scores than SeNPs (P = 0.013) and no difference from TA (P = 0.65). Histopathological analysis revealed that all treatments significantly reduced fibroplasia versus controls (P < 0.05). However, SeNTA exhibited the most favorable tissue profile, showing significantly reduced inflammation, collagen deposition, and vascularization compared to the TA and SeNPs groups (P < 0.05).

Conclusion: This leads to the conclusion that the simultaneous administration of tannic acid and SeNPs, both of which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory impacts, has been synergistically effective in controlling peritoneal adhesions.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Pathology, Selenium, Tannic Acid, Tissue Adhesion

Introduction

Adhesion after surgery is a critical challenge in abdominal surgery. Manipulation of the abdominal area during surgery and subsequent inflammation and adhesions can lead to several complications, including gastrointestinal stasis, abdominopelvic pain, acute bowel obstruction, infertility, and an increase in the length of the patient's hospitalization (1-3). Postoperative intra-abdominal adhesions represent a major clinical challenge with far-reaching implications for patient morbidity, healthcare resource utilization, and surgical outcomes. This necessitates the development of evidence-based preventive strategies to mitigate their substantial burden on individual patients and healthcare systems globally. Adhesions of intra-abdominal organs to the peritoneum have been reported to occur following laparotomy in 95% of patients (4). Complications from postoperative adhesions lead to approximately 50% of hospital readmissions following surgery, motivating widespread efforts to develop effective preventive measures (5). Key contributing factors include infection, thermal damage, ischemia, trauma, and foreign objects, which are the most common criteria that contribute to peritoneal adhesions after surgery (6).

Adhesions form through a process involving inflammatory reactions, fibrin deposition, and the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (7). The initial response to peritoneal injury involves the secretion of key signaling molecules, such as the cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, alongside other inflammatory mediators and growth factors. The stimulation results in mesothelial cell growth, angiogenesis, and fibroblast accumulation, which ultimately form adhesion bands. (8, 9). The literature describes a range of methods to prevent adhesions, including surgical approaches (laparoscopy), pharmacological interventions (antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], corticosteroids, thrombolytics), the use of surgical aids, and the intraperitoneal administration of therapeutic compounds (10, 11). Considering that post-operative oxidative stress is associated with the recruitment of neutrophils (12) and the reduction of fibrinolytic activity (13), ultimately leading to the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions, antioxidants are associated with reducing the level of oxidative stress and increasing post-surgery activities. MMP may help reduce postoperative abdominal adhesions (PAA) (14).

Therefore, any compound or drug with antioxidant effects has the potential to inhibit PAA. One of these compounds is selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), which have anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes and their possible negative effects and suppressing the immune system (15). It has been stated that SeNPs have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune system regulation effects, and by reducing some inflammatory factors, such as cytokines (such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), IL-1𝛽, and TNF-𝛼) and by-products of lipid peroxidation, they reduces the number of leukocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes and reduce pain. In addition, it prevents monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, neutrophil migration, and lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells (15). Therefore, it seems that the intraperitoneal administration of these nanoparticles can potentially treat adhesions after abdominal surgery. Tannic acid has a good anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effect (16, 17). The inhibition of fibrosis by tannic acid (TA) is partly attributable to its role in controlling persistent phospho-signaling downstream of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β stimulus (18).

Given the limited efficacy and potential adverse effects of current adhesion prevention strategies, the exploration of biocompatible nanomaterials, such as SeNPs combined with natural polyphenolic compounds, such as TA, offers a promising therapeutic paradigm that leverages targeted anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms to address the underlying pathophysiological processes of adhesion formation. Therefore, considering the anti-inflammatory impacts and decrease in cytokines and cells involved in the inflammatory process by TA and SeNPs, the present study investigated their intraperitoneal administration to control post-operative peritonitis and adhesions.

Methods

The current animal experimental study was conducted per the scientific and ethical guidelines approved by the Scientific and Research Council of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Shahrekord University. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Board of Research of Shahrekord University (Approval No. IR.SKU.REC.1402.059).

Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) and Tannic Acid

A solution was prepared by dissolving 100 mg of chitosan in 100 mL of 1% acetic acid, followed by adding 387 mg of ascorbic acid. The obtained solution was rotated at 500 rpm, and 5 mL of an 11 mg/mL solution of sodium selenite was added drop by drop. The obtained nanoparticles were washed several times with distilled water and characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and dynamic light scattering (DLs) methods.

Loading Nanoparticles with Tannic Acid (TA)

The obtained nanoparticles were dispersed in 30 mL of sterile normal saline, 600 mg of tannic acid was added, and the mixture was esterified for 24 hours. Finally, 0.25 mL of the final solution containing 0.2 mg of SeNPs and 5 mg of tannic acid was used for intraperitoneal injection of each rat.

Animals and Groups

Figure 1 illustrates the study objectives and the in vivo experimental flowchart.

Figure 1. In Vivo Animal Experimental Flowchart

Thirty male Wistar rats (12 weeks old, 250–300 g) were obtained and kept in standard laboratory cages for seven days to adapt to the new environment and ensure their health. Then the rats were randomly allocated into five equal groups: sham group (only laparotomy of the rats was performed without scratching the cecum and experimental adhesion induction), control group (experimental adhesion induction without any therapeutic intervention), SeNPs group (after experimental adhesion induction, SeNPs (0.2 mg dissolved in 250 μL of sterile distilled water) were injected intraperitoneally), TA group (Intraperitoneal injection of tannic acid (5 mg dissolved in 250 μL of sterile distilled water) followed by experimental induction of peritoneal adhesions), and selenium nano tanic acid (SeNTA) group (intraperitoneal injection of SeNPs (1 mg/kg) loaded with tannic acid (20 mg/kg) following experimental induction of intra-peritoneal adhesions).

Induction of Experimental Peritonitis Peritoneal Adhesions

After anesthesia induction by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), the abdominal surface of the rats was clipped and prepared aseptically using standard surgical protocols. To perform a laparotomy, a 3-cm incision was created along the linea alba (midline of the abdomen). After the cecum was exposed, the serosal surface of the cecum with dimensions of 1 x 2 cm was scratched using a soft nylon brush (cecum scratch model). The characteristic of this model is scratching for 30 seconds and the occurrence of petechial subserosal hemorrhages (19). After returning the cecum to the abdominal area, therapeutic injections were immediately performed in each group, based on the therapeutic approach (injection was repeated intraperitoneally, once a day, for 5 days). Finally, the abdominal area was

sutured in two routine layers with a simple continuous pattern and 0-3 synthetic thread. After the surgery, the rats were cared for in a warm and well-ventilated environment until full recovery and were kept in standard cages for 7 days.

Abdominal Adhesion Scoring

The rats were humanely euthanized seven days after surgery by administration of an overdose of anesthetics (by intraperitoneal administration, a dose 10 times higher than the ketamine-xylazine combination used for anesthesia in rats), and the abdominal cavity was accessed through a U-shaped incision, and full exploration was performed. Adhesion scoring of the abdominal area was performed blindly based on the study by Deng et al. (2020) (20). In this scoring system, a higher score indicates fewer adhesions.

Histopathological Examination

For histopathological evaluation, tissues affected by adhesion and the cecum wall (from the points with the most adhesion) were removed, washed with sterile normal saline, and placed in 10% formalin, to 5-6 μm tissue sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Fibroplasia, inflammation, vascularity and collagen

fiber parameters were scored in tissue sections. Points: 0 (absent); 1 (less than 50% visibility of the parameter compared to the control group), 2 (50-75% visibility of the parameter compared to the control group), and 3 (75% or more visibility of the parameter compared to the control group).

Statistical Analysis

A statistical Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to compare the groups' median adhesion scores and histological parameters. Subsequently, pairwise comparisons were made using the statistical Mann-Whitney U test as a post-hoc analysis, with a statistical significance level set at P < 0.05. The statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) was used for all analyses.

Results

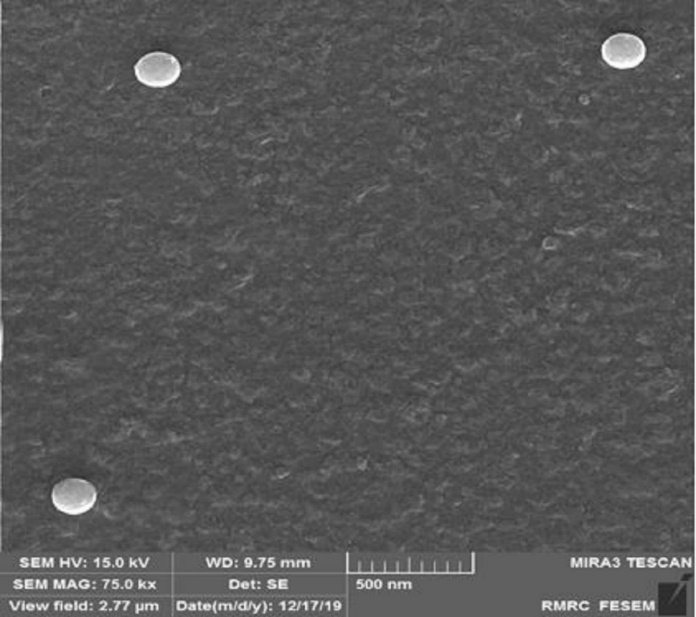

Morphological Characteristics of the Prepared Nanoparticles Using the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The results indicated that the synthesized particles were spherical, uniformly distributed, and had an average size of approximately 200 nm (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Image of Spherical Nanoparticles with Uniform Size Distribution (~200 nm)

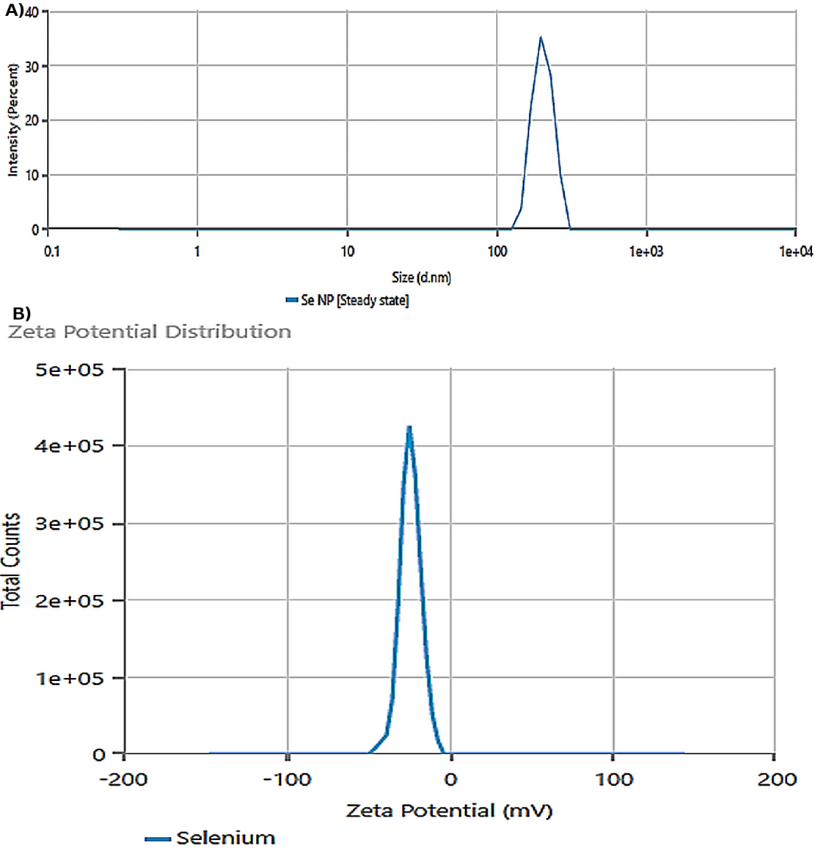

Evaluation of Nanoparticle Properties: Size, Distribution, and Zeta Potential

Based on the results obtained from DLS analysis, the size of the nanoparticles was estimated to be 205.4 nm, and the particle size distribution was 0.293, indicating the uniformity of the obtained particle sizes (Figure 3A). Also, the hydrodynamic diameter achieved by DLS was consistent with the size determined by SEM evaluation. The zeta potential of the obtained nanoparticles was equal to -23.84, the results of which are shown in Figure 3B.

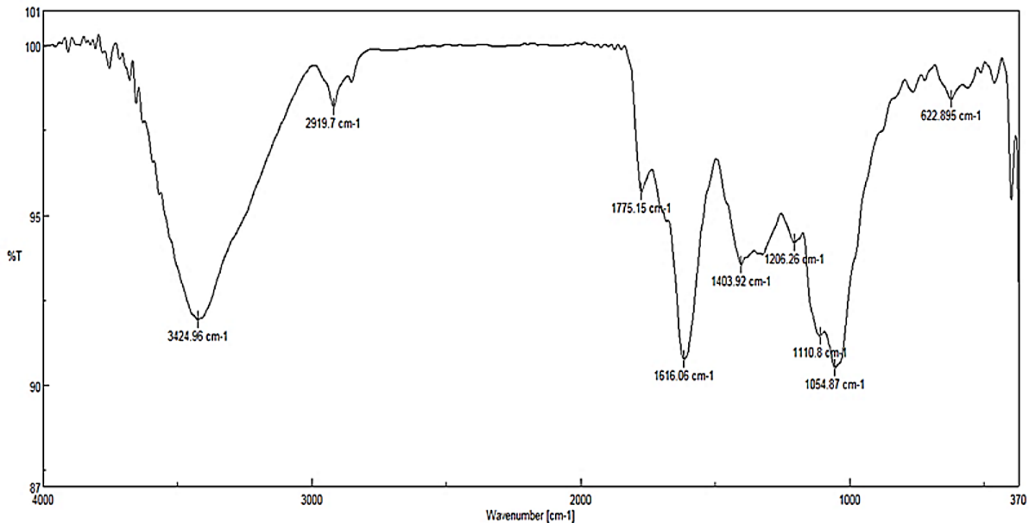

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Results of Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs)

Figure 4 illustrates FTIR results. The specific peak at 1054 cm-1 is associated with Se-O stretching vibration, and the peaks at 1616 and 470 cm-1 are associated with Se-O bending vibrations. High-intensity bands are present at 3424 cm-1, which are associated with O-H stretching and bending vibrations, respectively, and the peak at 1403 cm-1 is associated with C-O stretching vibration. The observed vibrations at 2870 cm-1 and 2919 cm-1 are associated with symmetric and asymmetric C-H stretching vibrations.

Figure 3. (A) Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Analysis Showing the Hydrodynamic Size Distribution of the Nanoparticles, With an Average Diameter of 205.4 nm and a Polydispersity Index (PDI) of 0.293, (B) Distribution of Nanoparticle Zeta Potentials, Indicating a Surface Charge of -23.84 mV

Figure 4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Spectrum of the Synthesized Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs)

Characteristic peaks confirm the presence of Se-O bonds (1054, 1616, and 470 cm⁻¹) and indicate the presence of surface functional groups, including O-H (3424 cm⁻¹), C-O (1403 cm⁻¹), and C-H (2870, 2919 cm⁻¹) vibrations.

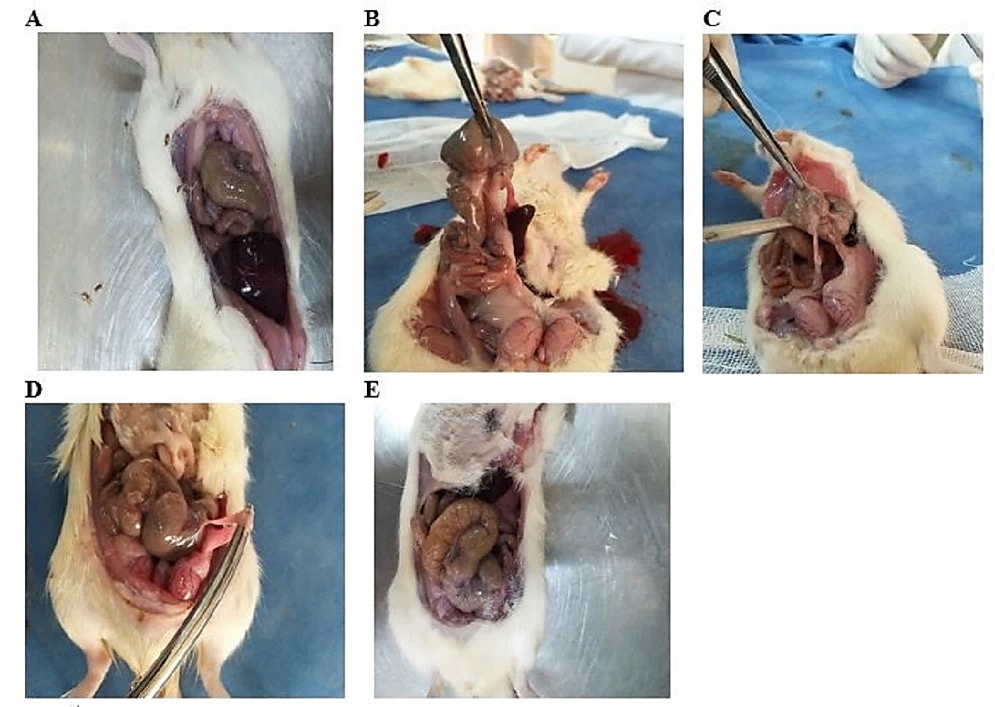

Abdominal Adhesion Scoring Results

After comparing the mean abdominal adhesion scores in different groups, Figure 5 illustrates the optimal images associated with the degree of adhesion in different individuals. Statistical comparison of the results revealed that adhesion in the control group was significantly higher than in the sham group (P = 0.006). Although no significant difference in adhesion was observed between the control and SeNPs groups (P = 0.121), the adhesion between the control group and TA and SeNTA groups was significantly higher (P = 0.01). The adhesion rate between the sham group and the TA and SeNTA groups was insignificant (P = 0.056). Abdominal adhesion in the SENPs group was significantly higher than in the TA and SeNTA groups (P = 0.013), but no statistically significant difference was observed between the TA and SeNTA groups (P = 0.65).

Figure 5. Different Degrees of Abdominal Adhesions; Sham Group (A); Control Group (B); Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) Group (C); Tanic Acid (TA) Group (D); Selenium Nano Tanic Acid (SeNTA) Group (E)

Histopathological Findings

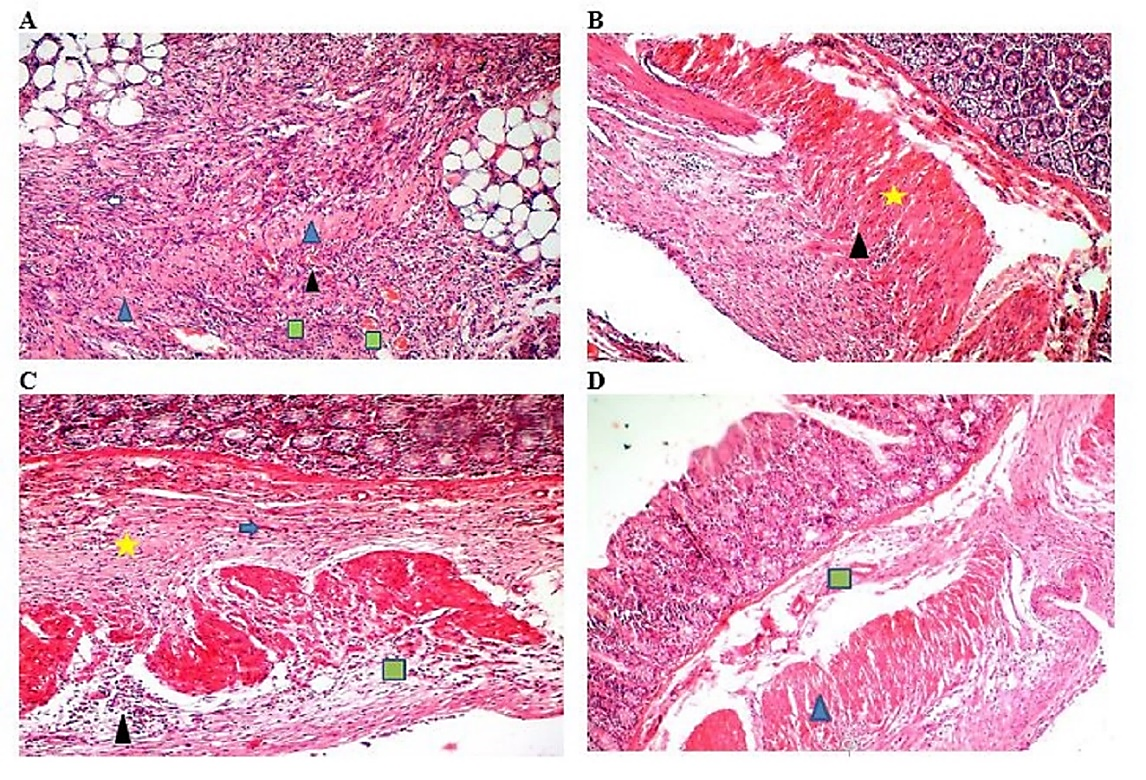

Table 1 and Figures 6 and 7 compare the histological characteristics of the experimental groups. The recorded data revealed no fibroplasia in the sham group, while most of the fibroplasia was detected in the control group.

Table 1. Median (Minimum-Maximum) Comparison of Histological Parameters in Different Groups

|

|

Fibroplasia |

Inflammation |

Collagen Fiber |

Vascularity |

|

Sham |

0 (0-0)a |

0 (0-1)a |

0 (0-0)a |

0 (0-0)a |

|

SeNTA |

1 (1-2)b |

1 (0-2)b |

1 (1-2)b |

1 (1-2)b |

|

TA |

2 (1-3)b |

2 (1-3)c |

2(2-3)c |

2 (1-3)c |

|

SeNPs |

2 (1-3)b |

2 (1-3)c |

2 (2-3)c |

2 (1-2)c |

|

Control |

3 (3-3)d |

3 (3-3)d |

3 (3-3)d |

3 (3-3)d |

Different letters within a column signifies statistically significant differences among the groups (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: SeNPs, selenium nanoparticles; TA, tannic acid; SeNTA, selenium nano tannic acid.

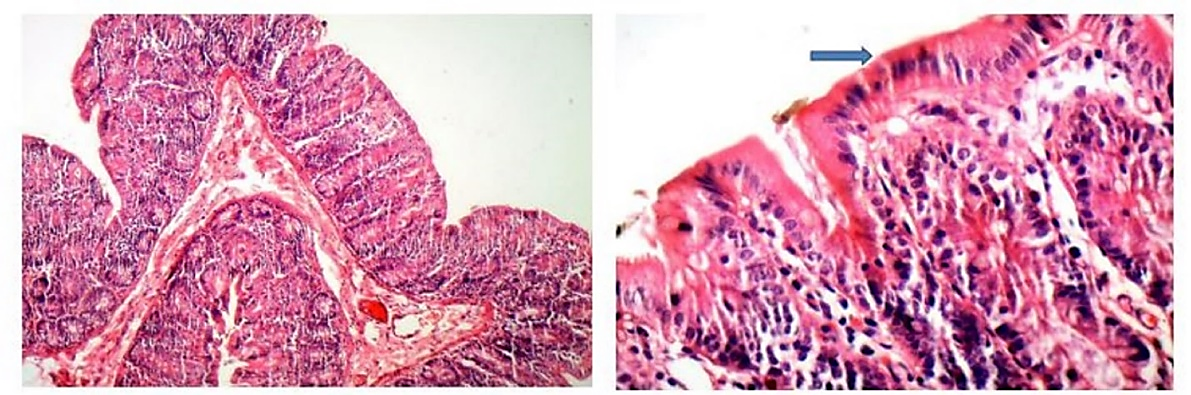

Figure 6. Tissue Section Prepared From Sham Group (10x Magnification)

The blue arrow indicates normal epithelial tissue. Inflammatory cells are not observed.

Figure 7. Control Group (10x Magnification) (A), Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) Group (10x Magnification) (B), Tannic Acid (TA) Group (10x Magnification) (C), SeNTA Group (10x Magnification) (D), Yellow Star: Collagen Fibers; Black Triangle: Inflammation; Green Square: Vascularity; Blue Triangle: Fibrosis; Blue Arrow: Fibroblast

Fibroplasia scores in the treatment groups (SeNTA, TA, and SeNPs) were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.05) but higher than those in the sham group, with no significant differences detected among the three treatment groups (P > 0.05). The results showed that the least inflammation, collagen fiber, and vessels were observed in the sham group, and the most of these parameters were observed in the control group. In addition, in the treatment groups, these tissue parameters in the SeNTA group were significantly lower than those in the TA and SeNPs groups (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The main causes of peritoneal adhesions are inflammation and infection after abdominal surgery (21, 22). Peritoneal injury triggers an inflammatory cascade mediated by macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts, ultimately leading to adhesion formation (23, 24). Following the release of injury-related molecular patterns from damaged peritoneal tissues or the stimulation of molecular patterns from bacteria, the peritoneal inflammatory response and peritoneal adhesions begin (25, 26).

The release of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α, from tissue cells and vascular endothelial cells facilitates the mobilization of neutrophils to the injured area (27, 28). In addition, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leads to the release of CXCL1 and CXCL2 from CD4+ T cells and mast cells, leading to the initial recruitment of neutrophils (29). These immune cells cause the creation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1) and collagen, stimulating the differentiation of peritoneal mesothelial cells into myofibroblasts and creating peritoneal adhesion (27). Also, releasing proteases and oxygen-free radicals increases peritoneal adhesion (30). Subsequently, by recruiting monocytes to the damaged area and transforming them into macrophages aligned with neutrophils, the inflammatory process in the peritoneum and the formation of peritoneal adhesions are intensified. The release of cytokines such as IL-23 and IL-12 from activated macrophages causes the activation of T lymphocytes and their differentiation into Th17 and Th1 cells. The secretion of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-17 cytokines from these T cells increases the peritoneal inflammatory response and can play a role in tissue repair and fibrosis (31). Among inflammatory cells, macrophages secrete TNF-α, interleukins 1 and 6, and TGF-β during phagocytosis and removal of cell debris. The result of these processes is the regulation of the inflammatory signaling of the peritoneum and the attraction and stimulation of other immune cells, and finally, the balance of the peritoneal immunity, the promotion of the inflammatory reaction and fibrosis, and the regeneration of the damaged peritoneum (32, 33).

TGF-β released from macrophages stimulates the extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis from fibroblasts (34). Removal of ECM within 5-7 days after peritoneal damage has been shown to prevent peritoneal adhesions. Otherwise, a fibrin matrix remains that gradually reorganizes with collagen-secreting fibroblasts and follows the growth of new vessels through angiogenic factors that develop peritoneal adhesions (1). The continuation of inflammatory reactions due to the activation and decomposition of prothrombin and conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin causes peritoneal adhesions (35). Following peritoneal injury, decreased tissue-type plasminogen activator and increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 released by macrophages and endothelial cells can delay fibrinolysis and lead to increased fibrin deposition and exacerbation of peritoneal fibrosis (36, 37). In addition, the production of fibrinolytic enzymes and the degradation of fibrin are limited by the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1) signal transduction pathway, which leads to the occurrence and development of peritoneal fibrosis (28). Considering the critical role of inflammation and oxidative damage in the occurrence of peritonitis and peritoneal adhesions, using any agent with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects can be considered a preventive and therapeutic approach in peritonitis and peritoneal adhesions. Our study demonstrated that SeNPs significantly reduced tissue parameters of fibroplasia, inflammation, collagen fiber formation, and vascularity compared to controls. This anti-inflammatory effect aligns with the known role of selenium in modulating key inflammatory pathways, which can limit peritoneal adhesion after peritoneal and abdominal injury. Similarly, the anti-inflammatory effect of selenium nanoparticle administration has been reported by Kaboutari et al. (2024). They reported that peritoneal exposure to SeNPs in rats with experimental peritoneal injury could decrease in TNF-α as a biomarker of peritonitis and peritoneal adhesion (38). By reducing the expression of L-selectin, SeNPs prevent neutrophil migration and lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. In addition, their immunomodulatory potential reduces the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages (39).

Also, the anti-inflammatory potential of SeNPs in reducing vascular inflammation by attenuating macrophage infiltration and inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) signaling pathways by Xiao et al. (2021) was reported (40). It has been found that the antioxidant potential of these nanoparticles is mediated by the direct inhibition of free radicals by increasing the activity of superoxide dismutase catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. In addition, SeNPs exert antioxidant effects by inhibiting lipid peroxidation (41). Various signaling pathways have been proposed for the anti-inflammatory effects of tannic acid. It has been found that SMAD2-dependent gene transcription subsequent to signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), TGF-β, and NF-κB pathways is inhibited by tannic acid, which leads to the anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects of tannic acid by reducing interleukin 1, 6, and 18, TNF-α, and COX-2 (42). In addition, the antioxidant effects of tannic acid have been reported to activate the Keap1-nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)/antioxidant response elements (ARE) signaling cascade and increase the levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), nitric oxide (NO), superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (43).

The mentioned mechanisms show the anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects of intraperitoneal administration of tannic acid in the current study. In the present study, the TA group showed a significant decrease in inflammation, fibroplasia, collagen formation, and vascularity, as well as a significantly lower degree of adhesion than the control group. The evaluation of tissue proinflammatory cytokines and long-term histopathological and gross evaluation of the effectiveness of the used compounds are limitations of the present study. Therefore, attention to long-term efficacy studies, dose optimization, combination with other preventive strategies, and translation to clinical trials can be considered a continuation of the present study.

Conclusions

The simultaneous administration of tannic acid and SeNPs, both possessing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, appears to have a synergistic effect in controlling peritoneal adhesions. This is supported by the significant reduction in histopathological parameters found in the SeNTA group compared to other groups, even though the macroscopic adhesion score showed no statistically significant difference between the TA and SeNTA groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Siavash Sharifi and Mr. Jamshid Kabiri for their support and coordination in conducting this research in the Section of Surgery and Radiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Shahrekord University.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article's research, authorship, or publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Received: 2025/07/21 | Accepted: 2025/09/27 | ePublished ahead of print: 2025/10/13 | Published: 2025/10/14

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |