Volume 13, Issue 4 (10-2025)

J Surg Trauma 2025, 13(4): 154-163 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahraki M, Khanlari S, Shafie Nikabadi F, Akhavanfard F. Early Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting and Lip Revision in Mixed Dentition: A Case Report. J Surg Trauma 2025; 13 (4) :154-163

URL: http://jsurgery.bums.ac.ir/article-1-512-en.html

URL: http://jsurgery.bums.ac.ir/article-1-512-en.html

Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 755 kb]

(615 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1203 Views)

Full-Text: (235 Views)

Abstract

Cleft defects are prevalent oromaxillofacial deformities, and surgical correction is essential for restoring oral function, improving speech, and enhancing facial aesthetics, thereby alleviating the social and communicative challenges experienced by affected children. A 7-year-old boy with a left cleft lip and palate received secondary alveolar bone grafting (SABG) using autologous iliac crest bone, plus a secondary lip revision after brief preoperative maxillary expansion. During follow-up, the oro-nasal gap was closed, speech was less hypernasal, and facial balance improved. Combining surgical, orthodontic, and restorative care helped address functional deficits and social concerns, which are outcomes after early secondary grafting in mixed dentition. However, close multidisciplinary coordination and setting realistic expectations remain crucial.

Key words: Alveolar bone grafting, Cleft lip, Cleft palate, Pediatric dentistry, Speech therapy

Cleft defects are prevalent oromaxillofacial deformities, and surgical correction is essential for restoring oral function, improving speech, and enhancing facial aesthetics, thereby alleviating the social and communicative challenges experienced by affected children. A 7-year-old boy with a left cleft lip and palate received secondary alveolar bone grafting (SABG) using autologous iliac crest bone, plus a secondary lip revision after brief preoperative maxillary expansion. During follow-up, the oro-nasal gap was closed, speech was less hypernasal, and facial balance improved. Combining surgical, orthodontic, and restorative care helped address functional deficits and social concerns, which are outcomes after early secondary grafting in mixed dentition. However, close multidisciplinary coordination and setting realistic expectations remain crucial.

Key words: Alveolar bone grafting, Cleft lip, Cleft palate, Pediatric dentistry, Speech therapy

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate are the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, affecting approximately 1.7 per 1000 births worldwide (1). These complex malformations occur from incomplete fusion of facial prominences during the fourth and tenth weeks of gestation. These disruptions can affect the primary palate (including the lip, alveolus, and anterior hard palate) or the secondary palate (the posterior hard and soft palates extending from the incisive foramen). Alveolar clefts, typically between the lateral incisor and canine teeth, are the main versions of these deformities and create considerable functional challenges beyond aesthetic problems (2).

Managing alveolar cleft defects requires comprehensive reconstructive approaches aimed at restoring anatomical continuity, providing adequate bone support for permanent tooth eruption, and facilitating closure of residual oro-antral communications (3). Secondary alveolar bone grafting (SABG), typically performed between ages 9 and 12 years, has emerged as the standard of care, with autogenous iliac crest bone grafts serving as the gold standard due to their superior osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties (4). Despite advances in grafting materials, including bone marrow concentrates and synthetic alternatives, autogenous iliac grafts remain the gold standard for their reliability in achieving successful bone integration. However, they are associated with resorption rates of 15%-24% within the first six months (5, 6).

Beyond structural reconstruction, alveolar bone grafting significantly impacts functional outcomes, particularly speech development and overall quality of life. Patients with untreated alveolar clefts frequently experience persistent speech difficulties, including hypernasal resonance, articulation disorders, and reduced intelligibility, which contribute to social stigmatization and diminished psychosocial well-being (7, 8).

Recent studies suggest that rebuilding the alveolus often leads to noticeable improvements in a child's speech, clearer speech, and reduced nasal resonance, and many families report an enhanced day-to-day quality of life. Some compensatory speech habits can persist even after surgery and typically require targeted speech therapy. Overall, the functional gains reinforce why timely, well-performed bone grafting is a key part of good cleft care (7, 9). Lu et al. reported that early SABG performed between 4 and 7 years of age resulted in superior outcomes compared to late SABG (8-12 years), demonstrating higher rates of bony bridge formation (77.3% vs. 65.4%) and lower Bergland scores (10). Based on the promising results of early grafting, we chose to perform the surgical intervention during the early graft placement period in this case. We present a case report highlighting improved speech and quality of life following cleft repair with iliac bone grafting.

Case

A 7-year-old boy was referred to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences to evaluate and manage residual cleft-related problems. His medical history reported no systemic conditions, allergies, or developmental delays. The patient was born with both lip and palatal clefts. There is no family history of cleft conditions. The couple's first son has congenital heart disease.

The patient underwent primary cleft lip repair (cheiloplasty) at five months, followed by palatoplasty at eight months. Despite these initial repairs, the patient currently presents with persistent facial edema and nasal regurgitation of fluids during drinking. Additionally, he experienced frequent otitis media and repeated chronic common colds. These functional deficits have significantly contributed to his psychosocial distress. His mother reported that, having started school, the patient had experienced hardship related to his facial appearance and difficulties with speech and feeding. Extraoral examination revealed a brachycephalic head form, and euryprosopic facial form with a straight profile. Facial asymmetry was evident, while the mentolabial sulcus appeared normal. His upper lip was short, and the lower lip was everted but complete at rest. A nasal examination revealed a wide alar base on the left side, a normal nasal bridge, and a deviation of the columella and nasal tip toward the right.

Cleft lip and palate are the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, affecting approximately 1.7 per 1000 births worldwide (1). These complex malformations occur from incomplete fusion of facial prominences during the fourth and tenth weeks of gestation. These disruptions can affect the primary palate (including the lip, alveolus, and anterior hard palate) or the secondary palate (the posterior hard and soft palates extending from the incisive foramen). Alveolar clefts, typically between the lateral incisor and canine teeth, are the main versions of these deformities and create considerable functional challenges beyond aesthetic problems (2).

Managing alveolar cleft defects requires comprehensive reconstructive approaches aimed at restoring anatomical continuity, providing adequate bone support for permanent tooth eruption, and facilitating closure of residual oro-antral communications (3). Secondary alveolar bone grafting (SABG), typically performed between ages 9 and 12 years, has emerged as the standard of care, with autogenous iliac crest bone grafts serving as the gold standard due to their superior osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties (4). Despite advances in grafting materials, including bone marrow concentrates and synthetic alternatives, autogenous iliac grafts remain the gold standard for their reliability in achieving successful bone integration. However, they are associated with resorption rates of 15%-24% within the first six months (5, 6).

Beyond structural reconstruction, alveolar bone grafting significantly impacts functional outcomes, particularly speech development and overall quality of life. Patients with untreated alveolar clefts frequently experience persistent speech difficulties, including hypernasal resonance, articulation disorders, and reduced intelligibility, which contribute to social stigmatization and diminished psychosocial well-being (7, 8).

Recent studies suggest that rebuilding the alveolus often leads to noticeable improvements in a child's speech, clearer speech, and reduced nasal resonance, and many families report an enhanced day-to-day quality of life. Some compensatory speech habits can persist even after surgery and typically require targeted speech therapy. Overall, the functional gains reinforce why timely, well-performed bone grafting is a key part of good cleft care (7, 9). Lu et al. reported that early SABG performed between 4 and 7 years of age resulted in superior outcomes compared to late SABG (8-12 years), demonstrating higher rates of bony bridge formation (77.3% vs. 65.4%) and lower Bergland scores (10). Based on the promising results of early grafting, we chose to perform the surgical intervention during the early graft placement period in this case. We present a case report highlighting improved speech and quality of life following cleft repair with iliac bone grafting.

Case

A 7-year-old boy was referred to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences to evaluate and manage residual cleft-related problems. His medical history reported no systemic conditions, allergies, or developmental delays. The patient was born with both lip and palatal clefts. There is no family history of cleft conditions. The couple's first son has congenital heart disease.

The patient underwent primary cleft lip repair (cheiloplasty) at five months, followed by palatoplasty at eight months. Despite these initial repairs, the patient currently presents with persistent facial edema and nasal regurgitation of fluids during drinking. Additionally, he experienced frequent otitis media and repeated chronic common colds. These functional deficits have significantly contributed to his psychosocial distress. His mother reported that, having started school, the patient had experienced hardship related to his facial appearance and difficulties with speech and feeding. Extraoral examination revealed a brachycephalic head form, and euryprosopic facial form with a straight profile. Facial asymmetry was evident, while the mentolabial sulcus appeared normal. His upper lip was short, and the lower lip was everted but complete at rest. A nasal examination revealed a wide alar base on the left side, a normal nasal bridge, and a deviation of the columella and nasal tip toward the right.

Clinical and Radiographic Findings

Clinical Examination

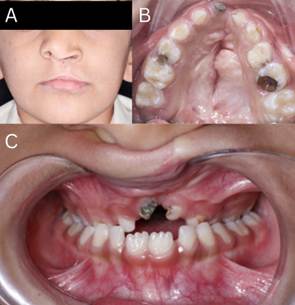

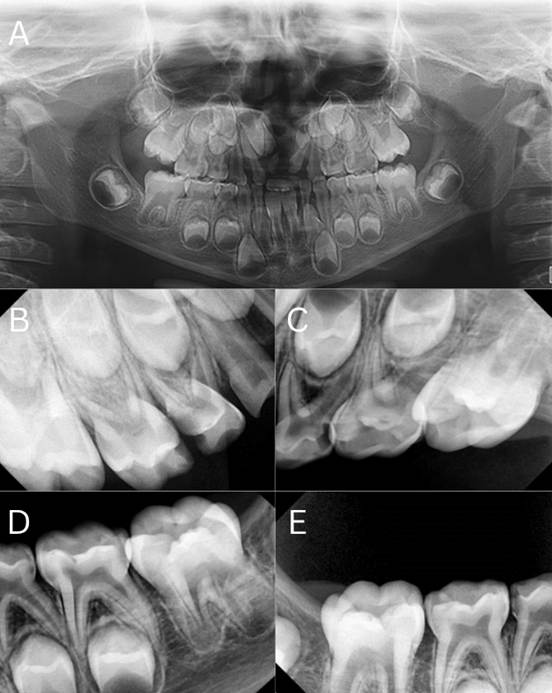

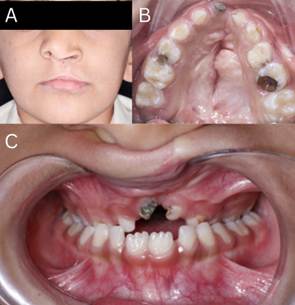

Clinical examination of a 7-year-old male revealed persistent residual deformity and functional impairment following primary cheiloplasty performed at five months of age. Extraorally, there was a residual lip asymmetry with a shortened upper lip, suggestive of scar contracture, accompanied by a nasal deformity apparent by deviation and visible asymmetry. Facial asymmetry was validated using cephalometric analysis. Intraoral examination demonstrated a complete unilateral left cleft of the palate and alveolus. The dental arch deviated toward the left, an anterior crossbite with reverse overjet, and bilateral posterior crossbites (Figure 1). Multiple carious lesions were present in the primary dentition and were addressed in phase 1 restorative care. An oro-nasal communication is clinically manifested by nasal regurgitation of fluids during drinking.

Figure 1. A) Facial Asymmetry with Lip and Nasal Deformity; B) Maxillary Arch with Unilateral Left Cleft and Leftward Deviation; C) Anterior and Bilateral Posterior Crossbites

Radiographic Assessment

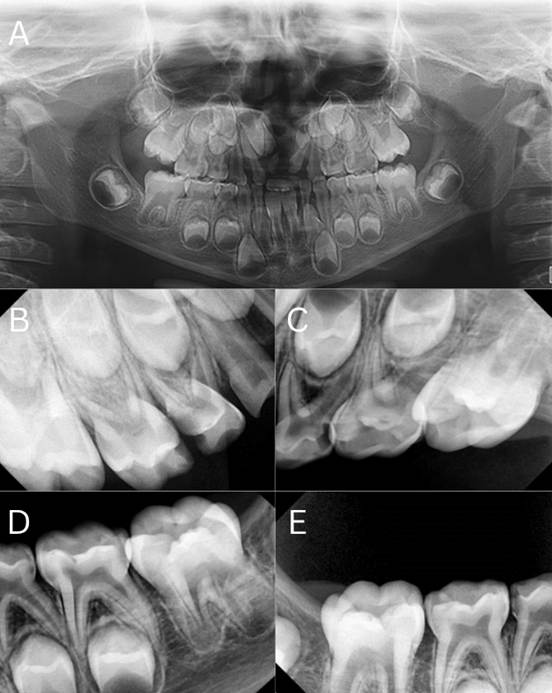

Radiographic assessment complemented the clinical findings. Panoramic radiography confirmed the congenital absence of the upper left central incisor (tooth 21). A series of periapical radiographs (PA) was obtained to evaluate the presence of radicular lesions, which revealed multiple primary molars requiring pulp therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A) Panoramic Radiograph Showing the Congenital Absence of the Upper Left Central Incisor and the Cleft in the Alveolar Bone, B) Periapical Radiographs (PA) of the Upper Right Quarter, C) PA of the Upper Left Quarter, D) PA of the Lower Left Quarter, E) PA of the Lower Right Quarter

Cephalometric analysis demonstrated maxillary deficiency with relative mandibular prognathism, an anterior crossbite with reverse overjet, bilateral posterior crossbites, a deep bite with clockwise mandibular rotation, a Class II molar relationship on the left side, and skeletal-vertical features consistent with facial asymmetry and a relatively short upper lip (Figure 3).

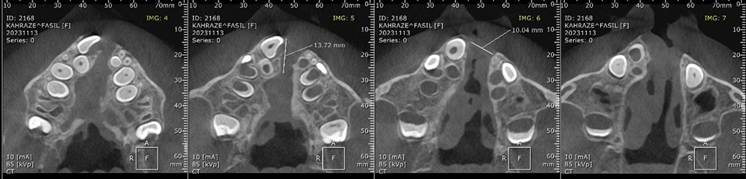

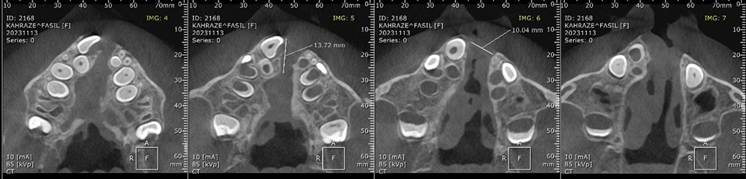

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) localized palatal and alveolar clefts in the anterior and midline regions, documented rotation of tooth 11, absence of tooth 21, and a peg-shaped tooth 22. CBCT measurements revealed a nasal cleft width of 4.5 mm anteriorly and 8.9 mm posteriorly, a vomero-chondral deformity with anterior nasal spine (ANS) deformity, and an alveolar cleft width of 10.4 mm at the central incisor region and 17.5 mm in the canine-to-canine span (Figure 4).

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) localized palatal and alveolar clefts in the anterior and midline regions, documented rotation of tooth 11, absence of tooth 21, and a peg-shaped tooth 22. CBCT measurements revealed a nasal cleft width of 4.5 mm anteriorly and 8.9 mm posteriorly, a vomero-chondral deformity with anterior nasal spine (ANS) deformity, and an alveolar cleft width of 10.4 mm at the central incisor region and 17.5 mm in the canine-to-canine span (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Cephalometric Analysis Showing Maxillary Deficiency, Mandibular Prognathism, Anterior and Bilateral Posterior Crossbites, and Deep Bite with Mandibular Rotation

Figure 4. Coronal Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Images Showing Palatal and Alveolar Clefts, Rotated Tooth 11, Absence of Tooth 21, and Measurements of Cleft Widths at the Nasal and Alveolar Regions

Diagnosis and Etiology

Based on the integrated clinical and radiographic data, the primary diagnosis was unilateral left complete cleft lip and palate with a secondary alveolar defect requiring alveolar bone grafting and secondary lip revision. Secondary diagnoses included congenital agenesis of the upper left central incisor, maxillary hypoplasia with anterior and bilateral posterior crossbites, and nasal deformity secondary to cleft deformity and associated vomero-chondral/ANS anomalies. These collective findings inform the need for a multidisciplinary treatment plan encompassing secondary soft-tissue revision (lip and potential nasal reconstruction), alveolar bone grafting guided by CBCT-derived defect dimensions, orthodontic intervention to correct transverse and sagittal mal-relationships and to prepare the dentition for grafting and prosthetic rehabilitation of the missing tooth, completion of dental restorative and endodontic care, and psychosocial support.

Treatment Protocol

Phase 1 treatment was performed under local anesthesia with supplemental behavior management techniques appropriate for pediatric patients. After a clinical and radiographic review, primary dental care consisted of endodontic, restorative, and extraction procedures to eliminate infection, restore function, and prepare the oral environment for subsequent reconstructive and orthodontic phases. Pulpotomies were performed on teeth 54, 55, 65, and 84 using a ferric sulfate hemostatic agent (DentoNext, Iran) and a formocresol-alternative protocol (Morvabon, Iran), followed by the placement of prefabricated stainless-steel crowns to provide long-term coronal seal and occlusal restoration. Teeth 64 and 53 received direct composite restorations using a total-etch adhesive system (37% phosphoric acid etch, adhesive bonding agent, OptiBond FL Kerr, Italy) and a light-cured nanohybrid composite resin to restore form and prevent further caries progression. Tooth 61, which exhibited non-restorable structural compromise, was atraumatically extracted. Hemostasis was achieved using local pressure and topical application of a resorbable gelatin sponge when required. All operative fields were isolated using cotton rolls and high-volume suction. Topical and infiltrative local anesthesia was administered (2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine, EXIR, Iran), with careful aspiration, and the dose was calculated according to the patient's weight. Postoperative instructions included analgesia with acetaminophen as needed, a soft diet for 24–48 hours, and topical oral hygiene measures.

Phase 2 (April 2024-December 2024): Phase 2 was instituted to correct transverse maxillary deficiency and complete interim restorative care in preparation for alveolar bone grafting and orthodontic alignment.

A W-arch palatal expansion appliance was fabricated and cemented. It was activated and monitored for nine months to achieve an adequate transverse maxillary width and dental arch form for subsequent alveolar bone grafting (Figure 5).

Phase 2 (April 2024-December 2024): Phase 2 was instituted to correct transverse maxillary deficiency and complete interim restorative care in preparation for alveolar bone grafting and orthodontic alignment.

A W-arch palatal expansion appliance was fabricated and cemented. It was activated and monitored for nine months to achieve an adequate transverse maxillary width and dental arch form for subsequent alveolar bone grafting (Figure 5).

Figure 5. W-arch Palatal Expansion Appliance Cemented for Transverse Maxillary Arch Form Preparation Before Alveolar Bone Grafting

Activation began in April with initial mesial contact of 25 mm and distal contact of 39 mm. The patient underwent regular orthodontic follow-up during this period. Subsequent observations and expansions were recorded in May, July, and October. In November, the appliance was maintained without further expansion. Finally, the appliance was removed in February 2025 in preparation for the surgical procedure. Throughout the treatment, activation protocols, retention periods, and appliance adjustments were documented during regular visits. The expansion aimed to correct bilateral posterior crossbite and create sufficient interdental space in the canine-to-canine region, facilitating graft placement and orthodontic tooth movement.

Fissure sealants: Teeth 16 and 26 received pit and fissure sealants using an etch-and-rinse technique (37% phosphoric acid etch, adhesive application, OptiBond FL Kerr, Italy) followed by placement of a light-cured resin sealant to prevent occlusal caries during the mixed dentition phase. Only these first permanent molars were treated because they were the only 6s that fully erupted and were suitable for complete isolation; the lower molars were not sufficiently erupted to allow for effective isolation. At the follow-up in December 2024, the lower molars received fissure sealants as they had erupted sufficiently.

Stainless steel crowns: Teeth 74 and 85 were restored with prefabricated stainless-steel crowns (KidsCrowns, Korea), following standard crown preparation under local anesthesia, to restore form and function and maintain posterior occlusion during arch development.

Pulp therapy and crown placement: Tooth 64 underwent pulpotomy using a biocompatible medicament (PRO ROOT MTA, Korea) and was restored with a stainless-steel crown (KidsCrowns, Korea) to ensure a durable coronal seal.

Composite restoration: Tooth 63 was restored with a direct composite restoration (Master Fill, Biodinamica, Brazil) using a total-etch adhesive protocol and a light-cured nanohybrid composite resin to reestablish the anterior form and prevent caries progression.

Expansion progress and transverse changes were monitored clinically and radiographically. The appliance successfully achieved the intended widening of the maxillary arch, correction of posterior crossbites, and creation of space in the alveolar cleft region to facilitate future grafting.

Restorative and endodontic interventions restored occlusal integrity and eliminated infection sources, thereby optimizing the oral environment before definitive reconstructive surgery.

The patient record documented all operative events, materials used, activation schedules, and postoperative instructions. Parents were counseled on appliance care, oral hygiene during expansion, and the necessity of continuing follow‑up to time the alveolar bone graft relative to dental development (Figure 6).

Fissure sealants: Teeth 16 and 26 received pit and fissure sealants using an etch-and-rinse technique (37% phosphoric acid etch, adhesive application, OptiBond FL Kerr, Italy) followed by placement of a light-cured resin sealant to prevent occlusal caries during the mixed dentition phase. Only these first permanent molars were treated because they were the only 6s that fully erupted and were suitable for complete isolation; the lower molars were not sufficiently erupted to allow for effective isolation. At the follow-up in December 2024, the lower molars received fissure sealants as they had erupted sufficiently.

Stainless steel crowns: Teeth 74 and 85 were restored with prefabricated stainless-steel crowns (KidsCrowns, Korea), following standard crown preparation under local anesthesia, to restore form and function and maintain posterior occlusion during arch development.

Pulp therapy and crown placement: Tooth 64 underwent pulpotomy using a biocompatible medicament (PRO ROOT MTA, Korea) and was restored with a stainless-steel crown (KidsCrowns, Korea) to ensure a durable coronal seal.

Composite restoration: Tooth 63 was restored with a direct composite restoration (Master Fill, Biodinamica, Brazil) using a total-etch adhesive protocol and a light-cured nanohybrid composite resin to reestablish the anterior form and prevent caries progression.

Expansion progress and transverse changes were monitored clinically and radiographically. The appliance successfully achieved the intended widening of the maxillary arch, correction of posterior crossbites, and creation of space in the alveolar cleft region to facilitate future grafting.

Restorative and endodontic interventions restored occlusal integrity and eliminated infection sources, thereby optimizing the oral environment before definitive reconstructive surgery.

The patient record documented all operative events, materials used, activation schedules, and postoperative instructions. Parents were counseled on appliance care, oral hygiene during expansion, and the necessity of continuing follow‑up to time the alveolar bone graft relative to dental development (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Preoperative Orthopantomography (OPG) Showing Pulpotomized and Crowned Primary Molars; Peg-Shaped Tooth 62 Planned for Extraction

Phase 3 (Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting (SABG) and Secondary Lip Revision): Preoperative CBCT confirmed adequate maxillary expansion achieved during Phase 2 and indicated optimal timing for SABG in the mixed-dentition stage, before permanent canine eruption. Standard pediatric fasting guidelines were observed preoperatively. Perioperative management followed accepted pediatric anesthetic protocols with anxiolysis and induction tailored to weight and cooperation: midazolam (0.5 mg/kg PO, max 15 mg, or 0.02 mg/kg IV, Darou Pakhsh Co., Iran) for premedication when indicated; induction with propofol (2.5 mg/kg IV, Diprivan, Sweden) or sevoflurane inhalational induction with spontaneous ventilation; maintenance with either propofol total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) (approximately 9 mg/kg/h) or sevoflurane (~2 MAC in O2/air); neuromuscular relaxation with cisatracurium (0.15 mg/kg for intubation with maintenance infusion at ~3 µg/kg/h when required, HMLAN, Germany); intraoperative analgesia utilizing fentanyl (1 µg/kg IV, JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICAL, Belgium) supplemented by acetaminophen (15 mg/kg IV, ALBORZDAROU, Iran) and, if indicated, morphine (0.1 mg/kg IV, Darou Pakhsh Co, Iran). Perioperative medications included antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin (25 mg/kg IV, maximum 2 g, Daana Pharma Co., Iran) administered pre-incision and dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg IV, maximum 10 mg, Darou Pakhsh Co., Iran) for its antiemetic and anti-inflammatory effects. Postoperative analgesia plans included ibuprofen (10 mg/kg PO, Pfizer, Advil, USA) when clinically appropriate.

Alveolar bone grafting was performed using autogenous cancellous bone harvested from the anterior iliac crest using the trapdoor technique. The patient was supine with a bolster under the ipsilateral hip to optimize access to the donor site. A 3‑cm incision was made approximately 3 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine, and the soft tissues were reflected with care to preserve periosteum and muscle attachments. A thin cortical wafer (2–3 mm) was elevated, and cancellous bone was harvested from the inner table using curettes. The harvested graft measured approximately 1.0 cm (width) × 2.0 cm (height) × 0.6 cm (thickness). The alveolar recipient site was exposed with sulcular and releasing incisions, cleft margins were debrided and refreshed, and the nasal mucosa was carefully closed to reestablish separation between the oral and nasal cavities. The autogenous graft was shaped to conform to the defect and secured into the alveolar cleft. Fixation was achieved with a 2‑mm titanium screw (Tenting screw, GBR, Korea), and particulate allograft bone (500–1000 mg, MBA Powder, Regen, Iran) was placed around the graft as augmentation. A resorbable barrier membrane (0.6–1.0 mm thickness, Tissue membrane, Regen, Iran) was positioned over the graft to promote guided bone regeneration. Tension-free mucosal closure was completed with resorbable sutures (Vicryl 4‑0, ATI MED, Iran), and donor site closure was performed in layers with resorbable deep sutures (Vicryl 3‑0, ATI MED, Iran) and fine skin sutures as indicated.

Concomitant secondary lip revision was performed using the Nadjmi technique (11) principles to correct residual lip asymmetry, scar contracture, and vermilion deficiency. Layered dissection separated skin, orbicularis oris muscle, and mucosa; scar adhesions were released, and the orbicularis oris muscle was mobilized and re-approximated across the midline using horizontal mattress sutures to restore sphincter function and central bulk. Local mucosal flaps were used as needed to reconstruct the nasal floor and ensure the oral and nasal cavities were separated. The vermilion tissue was advanced and reshaped to achieve improved contour and symmetry. The recommended suture protocol included Vicryl 4‑0 (ATI MED, Iran) for muscle repair, Monocryl 5‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) buried interrupted sutures for the deep dermis, and skin closure with nylon 6‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) or Prolene 6‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) interrupted sutures. The wet–dry vermilion junction was approximated with chromic gut 6‑0 when appropriate.

The intraoperative materials and instruments included a standard orthopedic bone-harvest tray, rongeurs and curettes for cancellous extraction, microsurgical instruments for delicate intraoral work, and fixation hardware (titanium screws). A piezoelectric bone unit was available for precision bone work when indicated. Hemostasis at the donor site was obtained, and the trapdoor cortical flap was repositioned and sutured to minimize donor-site morbidity. The fixation screw and membrane placement were documented, and copious irrigation and meticulous soft-tissue closure were emphasized to reduce the risk of infection.

Alveolar bone grafting was performed using autogenous cancellous bone harvested from the anterior iliac crest using the trapdoor technique. The patient was supine with a bolster under the ipsilateral hip to optimize access to the donor site. A 3‑cm incision was made approximately 3 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine, and the soft tissues were reflected with care to preserve periosteum and muscle attachments. A thin cortical wafer (2–3 mm) was elevated, and cancellous bone was harvested from the inner table using curettes. The harvested graft measured approximately 1.0 cm (width) × 2.0 cm (height) × 0.6 cm (thickness). The alveolar recipient site was exposed with sulcular and releasing incisions, cleft margins were debrided and refreshed, and the nasal mucosa was carefully closed to reestablish separation between the oral and nasal cavities. The autogenous graft was shaped to conform to the defect and secured into the alveolar cleft. Fixation was achieved with a 2‑mm titanium screw (Tenting screw, GBR, Korea), and particulate allograft bone (500–1000 mg, MBA Powder, Regen, Iran) was placed around the graft as augmentation. A resorbable barrier membrane (0.6–1.0 mm thickness, Tissue membrane, Regen, Iran) was positioned over the graft to promote guided bone regeneration. Tension-free mucosal closure was completed with resorbable sutures (Vicryl 4‑0, ATI MED, Iran), and donor site closure was performed in layers with resorbable deep sutures (Vicryl 3‑0, ATI MED, Iran) and fine skin sutures as indicated.

Concomitant secondary lip revision was performed using the Nadjmi technique (11) principles to correct residual lip asymmetry, scar contracture, and vermilion deficiency. Layered dissection separated skin, orbicularis oris muscle, and mucosa; scar adhesions were released, and the orbicularis oris muscle was mobilized and re-approximated across the midline using horizontal mattress sutures to restore sphincter function and central bulk. Local mucosal flaps were used as needed to reconstruct the nasal floor and ensure the oral and nasal cavities were separated. The vermilion tissue was advanced and reshaped to achieve improved contour and symmetry. The recommended suture protocol included Vicryl 4‑0 (ATI MED, Iran) for muscle repair, Monocryl 5‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) buried interrupted sutures for the deep dermis, and skin closure with nylon 6‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) or Prolene 6‑0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA) interrupted sutures. The wet–dry vermilion junction was approximated with chromic gut 6‑0 when appropriate.

The intraoperative materials and instruments included a standard orthopedic bone-harvest tray, rongeurs and curettes for cancellous extraction, microsurgical instruments for delicate intraoral work, and fixation hardware (titanium screws). A piezoelectric bone unit was available for precision bone work when indicated. Hemostasis at the donor site was obtained, and the trapdoor cortical flap was repositioned and sutured to minimize donor-site morbidity. The fixation screw and membrane placement were documented, and copious irrigation and meticulous soft-tissue closure were emphasized to reduce the risk of infection.

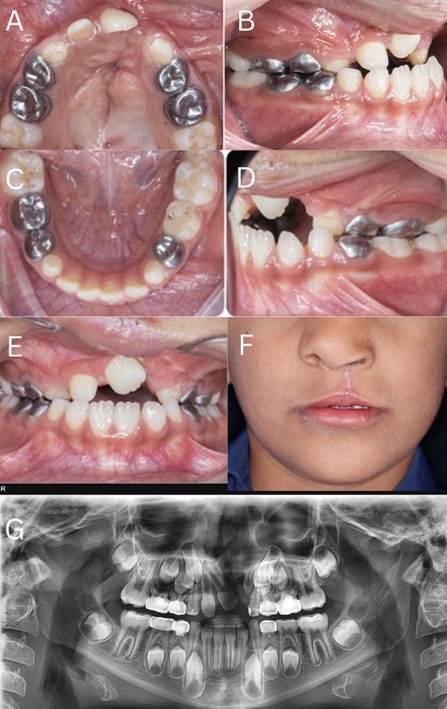

Follow-up and Outcome

The patient was recalled in August 2025 for follow-up after cleft repair with an iliac crest bone graft. The recovery has been steady, with complete resolution of fluid leakage into the nose and noticeable improvement in speech, characterized by reduced hypernasality. The posterior crossbite had largely resolved, except for the maxillary primary canines, which remained in crossbite but were expected to correct naturally after exfoliation.

The maxillary arch showed good healing at the cleft site with minimal residual scars. Despite maxillary expansion, some primary teeth still exhibit crossbite or tip-to-tip occlusion, while the mandibular arch maintains a well-formed shape with only mild anterior crowding. The remaining crossbites were primarily associated with unerupted permanent teeth, indicating the need for continued orthodontic monitoring.

Facial esthetics improved, with better lip support compared to the preoperative state. Radiographic evaluation suggested that orthodontic adjustments were necessary for the upper right central and lateral incisors to guide the proper eruption of the permanent canines. Following completion of maxillary growth, implant restoration was planned for the missing upper left central incisor to restore optimal function and appearance (Figure 7).

The maxillary arch showed good healing at the cleft site with minimal residual scars. Despite maxillary expansion, some primary teeth still exhibit crossbite or tip-to-tip occlusion, while the mandibular arch maintains a well-formed shape with only mild anterior crowding. The remaining crossbites were primarily associated with unerupted permanent teeth, indicating the need for continued orthodontic monitoring.

Facial esthetics improved, with better lip support compared to the preoperative state. Radiographic evaluation suggested that orthodontic adjustments were necessary for the upper right central and lateral incisors to guide the proper eruption of the permanent canines. Following completion of maxillary growth, implant restoration was planned for the missing upper left central incisor to restore optimal function and appearance (Figure 7).

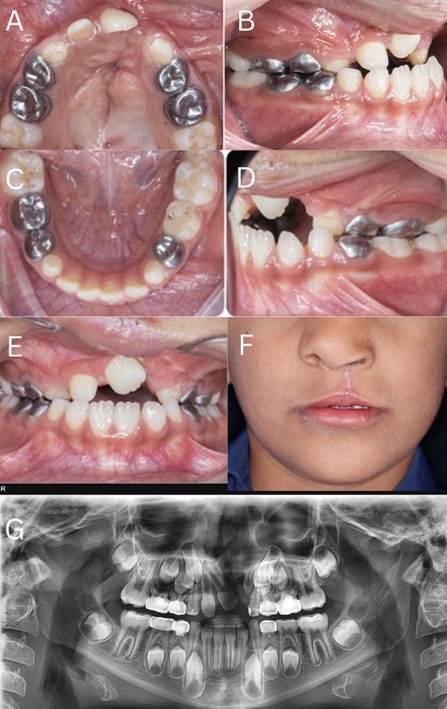

Figure 7. A) Upper-Arch Occlusal View Showing the Residual Cleft of the Maxilla, B) Right Lateral Occlusal/Bite View After Maxillary Expansion

Tooth 53 remained in crossbite, and tooth 52 was in an edge-to-edge (tip-to-tip) relationship.

C) Mandibular Occlusal View Demonstrating a Well-Formed Arch with Very Mild Anterior Crowding, D) Left Lateral Bite View Showing Persistent Crossbite of Tooth 63, E) Anterior Intraoral View Showing Residual Crossbite Primarily Attributable to Unerupted Permanent Teeth, F) Frontal Facial View Showing Improved Lip Support and Facial Esthetics Following Treatment, G) Postoperative Panoramic Radiograph

The upper right central and lateral incisors required orthodontic repositioning to guide the eruption of the permanent canines; the congenitally missing upper left central incisor was restored with an implant after maxillary growth was completed.

Discussion

The present case demonstrates successful SABG performed at 7 years of age, which aligns with contemporary recommendations for early SABG during the mixed dentition period. Lu et al. (10) found that early SABG (4-7 years) showed superior outcomes compared to late SABG (8-12 years), with higher rates of bony bridge formation (77.3% vs 65.4%) and lower Bergland scores. Similarly, the current case achieved complete resolution of oro-nasal communication and significant improvement in speech outcomes, supporting the effectiveness of early intervention. Mundra et al. (12) recommended grafting during the early mixed dentition phase between 6 and 8 years old, specifically before permanent central incisor eruption.

The present case used autogenous cancellous bone harvested from the anterior iliac crest using a trapdoor technique, the current gold standard for SABG procedures. The harvested graft was augmented with particulate allograft bone and covered with a resorbable barrier membrane. This combined approach aligns with current evidence supporting the use of autogenous iliac crest bone for its superior osteogenic properties. Pendem et al. (13) reported successful outcomes using a similar medially-based trap door approach in 28 pediatric patients, with harvested volumes ranging from 4 to 9 cc and minimal donor site morbidity. The technique demonstrated in this case achieved comparable results with complete resolution of functional deficits and improved facial aesthetics.

The use of supplemental particulate allografts in addition to autogenous bone is an evolving trend in SABG procedures. A recent systematic review by Todd et al. (14) compared conventional open techniques with minimally invasive approaches for iliac crest bone graft harvest, highlighting the importance of technique modification to minimize donor site morbidity while maintaining graft success rates. The current case demonstrated excellent donor site healing without complications, supporting the safety and efficacy of the trapdoor technique when properly executed. The combination of autogenous and allograft materials provides optimal graft volume while potentially reducing the harvest requirements from the donor site.

As demonstrated in this case, the simultaneous performance of SABG with secondary lip revision represents an efficient approach to comprehensive cleft reconstruction. The Nadjmi technique principles employed for lip revision significantly improved facial aesthetics and lip support, addressing both functional and cosmetic concerns. Rothermel et al. (15) evaluated patient-reported outcomes following secondary cleft lip and nasal revision procedures in 42 patients, finding significant improvements in lip appearance (1.93 score) and nose appearance (1.98 score), with overall patient satisfaction scores of 1.76. These findings align with the aesthetic improvements observed in the present case, in which frontal facial photography demonstrated enhanced lip support and improved facial symmetry.

The psychosocial benefits of combined surgical interventions cannot be understated, particularly in school-age children. The patient in this case experienced social challenges related to facial appearance and speech difficulties, which significantly improved following surgical intervention. Rothermel et al. (15) reported that patients experienced improved self-confidence, decreased self-consciousness, reduced peer teasing, and increased likelihood to participate in social activities following secondary revision procedures. The comprehensive approach demonstrated in this case, addressing both alveolar reconstruction and lip aesthetics simultaneously, optimizes both functional and psychosocial outcomes while minimizing the number of surgical interventions required.

The nine-month orthodontic preparation phase utilizing a W-arch palatal expansion appliance is a critical component of successful SABG outcomes. The expansion achieved adequate transverse maxillary width and created appropriate arch form for subsequent bone grafting, addressing the bilateral posterior crossbites present preoperatively. Contemporary evidence supports the importance of pre-grafting orthodontic preparation, with Mundra et al. (12) reporting that 80% of studies utilized orthodontic treatment concomitant with surgery, and 66.7% employed pre-operative orthodontics. The successful expansion demonstrated in this case facilitated optimal graft placement and subsequent tooth movements.

Managing a congenitally missing upper left central incisor represents a complex treatment planning challenge that requires long-term orthodontic and prosthodontic coordination. Aldosari et al. (16) recently compared orthodontic space closure versus space opening approaches for missing lateral incisors in cleft patients, finding comparable alveolar bone support between treatment modalities. Although the present case involved a missing central incisor rather than a lateral incisor, the space management principles remain relevant. The planned implant restoration following completion of maxillary growth represents an appropriate treatment approach that will require continued orthodontic monitoring to maintain adequate space and optimize tooth positioning for prosthetic restoration.

The complete resolution of nasal fluid leakage and significant improvement in speech hypernasality represent important functional achievements in this patient. The successful closure of the oro-nasal communication is fundamental to normal speech development and feeding function. Although specific speech assessment scores were not provided, the clinical improvement described is consistent with successful SABG outcomes reported in the literature. The maintenance of these functional improvements at the 8-month follow-up visit demonstrates the stability of the surgical reconstruction and the effectiveness of the chosen treatment approach.

Conclusions

The comprehensive treatment approach demonstrated in this case, incorporating early SABG with concurrent lip revision, pre-surgical orthodontic preparation, and planned long-term prosthetic rehabilitation, represents current best practice in cleft care. The successful outcomes support the continued use of early mixed dentition timing for SABG procedures, combined surgical approaches for efficiency, and the importance of multidisciplinary treatment planning. This case demonstrates that a well-executed SABG with appropriate timing and technique can achieve excellent functional and aesthetic outcomes while minimizing patient morbidity and improving quality of life.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

C) Mandibular Occlusal View Demonstrating a Well-Formed Arch with Very Mild Anterior Crowding, D) Left Lateral Bite View Showing Persistent Crossbite of Tooth 63, E) Anterior Intraoral View Showing Residual Crossbite Primarily Attributable to Unerupted Permanent Teeth, F) Frontal Facial View Showing Improved Lip Support and Facial Esthetics Following Treatment, G) Postoperative Panoramic Radiograph

The upper right central and lateral incisors required orthodontic repositioning to guide the eruption of the permanent canines; the congenitally missing upper left central incisor was restored with an implant after maxillary growth was completed.

Discussion

The present case demonstrates successful SABG performed at 7 years of age, which aligns with contemporary recommendations for early SABG during the mixed dentition period. Lu et al. (10) found that early SABG (4-7 years) showed superior outcomes compared to late SABG (8-12 years), with higher rates of bony bridge formation (77.3% vs 65.4%) and lower Bergland scores. Similarly, the current case achieved complete resolution of oro-nasal communication and significant improvement in speech outcomes, supporting the effectiveness of early intervention. Mundra et al. (12) recommended grafting during the early mixed dentition phase between 6 and 8 years old, specifically before permanent central incisor eruption.

The present case used autogenous cancellous bone harvested from the anterior iliac crest using a trapdoor technique, the current gold standard for SABG procedures. The harvested graft was augmented with particulate allograft bone and covered with a resorbable barrier membrane. This combined approach aligns with current evidence supporting the use of autogenous iliac crest bone for its superior osteogenic properties. Pendem et al. (13) reported successful outcomes using a similar medially-based trap door approach in 28 pediatric patients, with harvested volumes ranging from 4 to 9 cc and minimal donor site morbidity. The technique demonstrated in this case achieved comparable results with complete resolution of functional deficits and improved facial aesthetics.

The use of supplemental particulate allografts in addition to autogenous bone is an evolving trend in SABG procedures. A recent systematic review by Todd et al. (14) compared conventional open techniques with minimally invasive approaches for iliac crest bone graft harvest, highlighting the importance of technique modification to minimize donor site morbidity while maintaining graft success rates. The current case demonstrated excellent donor site healing without complications, supporting the safety and efficacy of the trapdoor technique when properly executed. The combination of autogenous and allograft materials provides optimal graft volume while potentially reducing the harvest requirements from the donor site.

As demonstrated in this case, the simultaneous performance of SABG with secondary lip revision represents an efficient approach to comprehensive cleft reconstruction. The Nadjmi technique principles employed for lip revision significantly improved facial aesthetics and lip support, addressing both functional and cosmetic concerns. Rothermel et al. (15) evaluated patient-reported outcomes following secondary cleft lip and nasal revision procedures in 42 patients, finding significant improvements in lip appearance (1.93 score) and nose appearance (1.98 score), with overall patient satisfaction scores of 1.76. These findings align with the aesthetic improvements observed in the present case, in which frontal facial photography demonstrated enhanced lip support and improved facial symmetry.

The psychosocial benefits of combined surgical interventions cannot be understated, particularly in school-age children. The patient in this case experienced social challenges related to facial appearance and speech difficulties, which significantly improved following surgical intervention. Rothermel et al. (15) reported that patients experienced improved self-confidence, decreased self-consciousness, reduced peer teasing, and increased likelihood to participate in social activities following secondary revision procedures. The comprehensive approach demonstrated in this case, addressing both alveolar reconstruction and lip aesthetics simultaneously, optimizes both functional and psychosocial outcomes while minimizing the number of surgical interventions required.

The nine-month orthodontic preparation phase utilizing a W-arch palatal expansion appliance is a critical component of successful SABG outcomes. The expansion achieved adequate transverse maxillary width and created appropriate arch form for subsequent bone grafting, addressing the bilateral posterior crossbites present preoperatively. Contemporary evidence supports the importance of pre-grafting orthodontic preparation, with Mundra et al. (12) reporting that 80% of studies utilized orthodontic treatment concomitant with surgery, and 66.7% employed pre-operative orthodontics. The successful expansion demonstrated in this case facilitated optimal graft placement and subsequent tooth movements.

Managing a congenitally missing upper left central incisor represents a complex treatment planning challenge that requires long-term orthodontic and prosthodontic coordination. Aldosari et al. (16) recently compared orthodontic space closure versus space opening approaches for missing lateral incisors in cleft patients, finding comparable alveolar bone support between treatment modalities. Although the present case involved a missing central incisor rather than a lateral incisor, the space management principles remain relevant. The planned implant restoration following completion of maxillary growth represents an appropriate treatment approach that will require continued orthodontic monitoring to maintain adequate space and optimize tooth positioning for prosthetic restoration.

The complete resolution of nasal fluid leakage and significant improvement in speech hypernasality represent important functional achievements in this patient. The successful closure of the oro-nasal communication is fundamental to normal speech development and feeding function. Although specific speech assessment scores were not provided, the clinical improvement described is consistent with successful SABG outcomes reported in the literature. The maintenance of these functional improvements at the 8-month follow-up visit demonstrates the stability of the surgical reconstruction and the effectiveness of the chosen treatment approach.

Conclusions

The comprehensive treatment approach demonstrated in this case, incorporating early SABG with concurrent lip revision, pre-surgical orthodontic preparation, and planned long-term prosthetic rehabilitation, represents current best practice in cleft care. The successful outcomes support the continued use of early mixed dentition timing for SABG procedures, combined surgical approaches for efficiency, and the importance of multidisciplinary treatment planning. This case demonstrates that a well-executed SABG with appropriate timing and technique can achieve excellent functional and aesthetic outcomes while minimizing patient morbidity and improving quality of life.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Type of Study: Case Report |

Subject:

Pediatric

Received: 2025/09/22 | Accepted: 2025/10/5 | ePublished ahead of print: 2025/10/13 | Published: 2025/10/14

Received: 2025/09/22 | Accepted: 2025/10/5 | ePublished ahead of print: 2025/10/13 | Published: 2025/10/14

References

1. Rahimov F, Nieminen P, Kumari P, Juuri E, Nikopensius T, Paraiso K, et al. High incidence and geographic distribution of cleft palate in Finland are associated with the IRF6 gene. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9568. [DOI:10.1038/s41467-024-53634-2]

2. Lewis CW, Jacob LS, Lehmann CU. The Primary Care Pediatrician and the Care of Children With Cleft Lip and/or Cleft Palate. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5). [DOI:10.1542/peds.2017-0628]

3. Joos U, Markus AF, Schuon R. Functional cleft palate surgery. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2023;13(2):290-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jobcr.2023.02.003]

4. Seifeldin SA. Is alveolar cleft reconstruction still controversial? (Review of literature). Saudi Dent J. 2016;28(1):3-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.sdentj.2015.01.006]

5. Mertens C, Decker C, Seeberger R, Hoffmann J, Sander A, Freier K. Early bone resorption after vertical bone augmentation--a comparison of calvarial and iliac grafts. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24(7):820-5. [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02463.x]

6. Naujokat H, Loger K, Gülses A, Flörke C, Acil Y, Wiltfang J. Effect of enriched bone-marrow aspirates on the dimensional stability of cortico-cancellous iliac bone grafts in alveolar ridge augmentation. International journal of implant dentistry. 2022;8(1):34. [DOI:10.1186/s40729-022-00435-1]

7. Prathanee B, Buakanok N, Pumnum T, Thanawirattananit P. Hearing, speech, and language outcomes in school-aged children after cleft palate repair. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2024;25(5):230-9. [DOI:10.7181/acfs.2024.00395]

8. Crowley CJ. Improving Speech Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries for Patients Born with Cleft Palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025;156(4s-2):14s-22s. [DOI:10.1097/PRS.0000000000012374]

9. Inchingolo AM, Dipalma G, Bassi P, Lagioia R, Cavino M, Colonna V, et al. Evaluation of Surgical Protocols for Speech Improvement in Children with Cleft Palate: A Systematic Review and Case Series. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025;12(8). [DOI:10.3390/bioengineering12080877]

10. Lu X, Roohani I, Manasyan A, Stanton EW, Youn S, Hammoudeh JA, et al. Comparing Three-dimensional Radiologic Outcomes Between Early Versus Late Secondary Alveolar Bone Grafting. J Craniofac Surg. 2025;36(1):78-83. [DOI:10.1097/SCS.0000000000010676]

11. Nadjmi N, Vaes L, Van de Casteele E. A novel technique for nasal alar reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery-Global Open. 2022;10(4):e4284. [DOI:10.1097/GOX.0000000000004284]

12. Mundra LS, Lowe KM, Khechoyan DY. Alveolar Bone Graft Timing in Patients With Cleft Lip & Palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33(1):206-10. [DOI:10.1097/SCS.0000000000007890]

13. Pendem S, Selvarasu K, Krishnan M, Kumar SP, Bhuvan Chandra R. Anatomical Basis for Preservation of Cartilaginous Apophysis in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Iliac Crest Bone Graft Harvest: A Cohort Study. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58020. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.58020]

14. Todd AR, Fitzpatrick S, Cawthorn TR, Fraulin FOG, Robertson Harrop A. Iliac Crest Bone Graft Harvest for Alveolar Cleft Repair: A Systematic Review Comparing Minimally Invasive Trephine and Conventional Open Techniques. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2024;32(1):78-85. [DOI:10.1177/22925503221088840]

15. Rothermel A, Loloi J, Long RE, Jr., Samson T. Patient-Centered Satisfaction After Secondary Correction of the Cleft Lip and Nasal Defect. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020;57(7):895-9. [DOI:10.1177/1055665619901183]

16. Aldosari M, Shah J, Ko J, Oberoi S. Alveolar Bone Quality in Individuals With Cleft Lip and Palate With Missing Lateral Incisors: Orthodontic Space Closure Versus Space Opening. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2025:10556656241312499. [DOI:10.1177/10556656241312499]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |